In a state-of-the-art museum and conservation lab in Newport News, Virginia, sit large tanks of fresh water that hold large rusting chunks of iron that are over 150 years old. 150 years isn’t a long time for some museum artifacts; in Manhattan one can visit the Metropolitan Museum and see Buddhist statues over 500 years old, then walk several yards down the hall and see mummies thousands of years old. But the significance of the rusted iron from USS Monitor that rests in The Mariner’s Museum in Virginia isn’t in its age; it’s in the revolution that it brought.

In a state-of-the-art museum and conservation lab in Newport News, Virginia, sit large tanks of fresh water that hold large rusting chunks of iron that are over 150 years old. 150 years isn’t a long time for some museum artifacts; in Manhattan one can visit the Metropolitan Museum and see Buddhist statues over 500 years old, then walk several yards down the hall and see mummies thousands of years old. But the significance of the rusted iron from USS Monitor that rests in The Mariner’s Museum in Virginia isn’t in its age; it’s in the revolution that it brought.

The battle between USS Monitor and CSS Virginia 150 years ago today is one of the few naval battles, besides Pearl Harbor, that most people have heard of. Monitor and Virginia were not the first ironclad warships in the world, not even the first in the Civil War. They were, however, the first to face off ironclad vs. ironclad. The long and largely indecisive battle of March 9th, 1862, in Hampton Roads, proved the worth of their armor against enemy fire, and changed warfare forever. The day Prior Virginia had run amok amid the Union fleet of wooden warships there, sinking USS Congress and USS Cumberland with heavy loss of life. It was the worst defeat the U.S. Navy had ever suffered, and the day would retain that title until 1941 and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Indeed, many leaders around the world said the havoc Virginia wrought on the wooden ships, and the following day’s meeting of the two ironclad ships, meant that all other navies in the world were instantly obsolete.

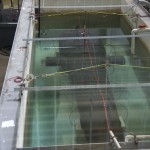

At The Mariner’s Museum they keep the large metal artifacts in large flooded tanks, In order to keep the saltwater permeated metal components from breaking down in the atmosphere. This past fall I found out that they’d be draining the turret’s tank for inspection and conservation, so I dragged my wife Kristen along and we drove the six hours to Virginia.

My first interest in these ships started in Junior High history class, while studying the Civil War. I was already into ships by then, and I asked my teacher why the history book referred to the fight as the duel between the Monitor and the Merrimack, when the Confederate ship was clearly named the Virginia. He had no answer. I had to research on my own – in the long run a good outcome! – to find out that USS Merrimack was a wooden U.S. Navy steam warship that was scuttled when the Norfolk Navy Yard was evacuated, to keep the Confederates from getting hold of her. She sank to the bottom and everything above the waterline burned. The lower hull, and her engines were fine, however, so the Confederates converted her to an ironclad. She was commissioned into the Confederate Navy with the name Virginia, but northern sources continued to refer to her as Merrimack.

My first interest in these ships started in Junior High history class, while studying the Civil War. I was already into ships by then, and I asked my teacher why the history book referred to the fight as the duel between the Monitor and the Merrimack, when the Confederate ship was clearly named the Virginia. He had no answer. I had to research on my own – in the long run a good outcome! – to find out that USS Merrimack was a wooden U.S. Navy steam warship that was scuttled when the Norfolk Navy Yard was evacuated, to keep the Confederates from getting hold of her. She sank to the bottom and everything above the waterline burned. The lower hull, and her engines were fine, however, so the Confederates converted her to an ironclad. She was commissioned into the Confederate Navy with the name Virginia, but northern sources continued to refer to her as Merrimack.

Virginia was more of a traditional ship, with a large gun deck like the sailing ships that had ruled the seas for centuries, multiple guns in a broadside. Monitor, a technological marvel designed by John Ericsson — a true genius if one ever existed — was unique in many ways; she had nearly 100 different patentable inventions in her innards, including the world’s first toilet that could flush even though it was installed below the waterline. But it was her rotating turret for which she is most recognized. Again, this was not a new idea, but Ericsson’s design for Monitor was the first to really make it work, and to use it in combat. The turret and its ability to rotate and aim no matter the direction of the ship made Monitor’s two guns the equivalent of Virginia’s ten broadside guns.

It’s Monitor’s turret that’s the centerpiece of the collection at The Mariner’s Museum. When we arrived that day last fall I had a pretty good idea of what I’d see once the water had been drained away: Large thick sheets of iron, huge bolts holding them together, iron crossbeams for support, and all of it a rusty reddish-brown and roughly textured. The distance the museum keeps visitors probably reduces the impact of the items for most viewers, but to me it was like being transported back to when the metal was still newly rolled, painted black, and on a tossing flat deck. Other tanks sit in the conservation room, holding the monitor’s engine and the two guns that came out of the turret.

It’s Monitor’s turret that’s the centerpiece of the collection at The Mariner’s Museum. When we arrived that day last fall I had a pretty good idea of what I’d see once the water had been drained away: Large thick sheets of iron, huge bolts holding them together, iron crossbeams for support, and all of it a rusty reddish-brown and roughly textured. The distance the museum keeps visitors probably reduces the impact of the items for most viewers, but to me it was like being transported back to when the metal was still newly rolled, painted black, and on a tossing flat deck. Other tanks sit in the conservation room, holding the monitor’s engine and the two guns that came out of the turret.

Both Monitor and Virginia had short lives. Virginia was blown up later in the year to avoid capture as the Union retook the Hampton Roads area, and was likely salvaged in place for her valuable iron in the years immediately after the war. In a classic example of Nature over Technology, Monitor sank in a heavy storm off the coast of Cape Hatteras, NC. on December 31st of that same year. Hours of sustained gunfire could only dent her armor, but a heavy sea state flooded her and took her to the bottom quickly. Monitor was found in 1973 and designated a marine sanctuary to preserve her remains. Besides her turret, guns and engine, other parts have already been restored and are on display, including her massive screw (propeller), anchor, and her famous red lantern.

The battle between Monitor and Virginia 150 years ago today revolutionized naval combat. More than that, it was another instance of the modernization of the world at large. The leaders of the Civil War wouldn’t realize the costs of using modern technology with an old mindset for several years, a mistake that would result in hundreds of thousands of deaths on the battlefields of North America. But once the true capabilities of ships like Monitor, weapons like the rifled bullet, air observation by balloon, and battlefield communications via telegraph, were taken out of the classic Napoleonic and Nelsonic context (Is Nelsonic a word? It is now), and allowed to inhabit their own space in the world, they would change that world. And it wouldn’t be just the weapons, but the industry behind them and the support structures they required (remember those 100 patentable inventions in USS Monitor that made her run?). Factories were required to up their quality control so that all rifles were exactly the same so that parts were interchangeable. Foundries had to retool to keep up with the rolled iron sheets for armor for the glut of ironclads ordered after the Hampton Roads battle. An entirely new infrastructure had to be built to feed the hundreds of thousands of soldiers and sailors, and then to care for the wounded. All if this stabilized the groundwork for the industrial revolution that had already begun, and would take off at an incredible rate once Americans stopped fighting one another.

Seeing the massive rusted turret last fall was an amazing experience, and my wife even seemed to be impressed. While I look forward to the day that the preservation work on Monitor’s turret is complete and visitors can walk up to the massive cylinder and see it as it once was. I have to admit, though, that I’ll miss seeing all of that rusted metal, the 150 years of age still clinging visibly to the iron. It’s a great reminder of when such things were new to the world, and how we were just beginning to realize how far we could go.

Note: There are tons of books on the battle between Monitor and Virgina, one of the best of which in my opinion is REIGN OF IRON ; a most comprehensive treatment of the entire two day engagement that also does a marvelous job of detailing the construction of both warships.

The current state of Monitor’s turret and other artifacts are best followed-up with at the source: The Mariner’s Museum

Pingback: , Archive