June 1863 saw messages and telegraph traffic explode to new levels as the North and the Army of the Potomac anticipated General Lee’s next move. Many expected Lee, fresh from victory at Chancellorsville, to go on the offensive. The North, wounds still knitting from that battle, reorganized and prepared to match Lee’s movements. Many enlistments in the Army of the Potomac had expired on June 1st, and many one year and ninety-day men went home. The draw down in man power and influx of new units saw the Iron Brigade re-designated as the First Brigade of the First Division of the First Corps of the Army of the Potomac. They would now be first on paper, as well as first on the field, in the coming campaign.

June 1863 saw messages and telegraph traffic explode to new levels as the North and the Army of the Potomac anticipated General Lee’s next move. Many expected Lee, fresh from victory at Chancellorsville, to go on the offensive. The North, wounds still knitting from that battle, reorganized and prepared to match Lee’s movements. Many enlistments in the Army of the Potomac had expired on June 1st, and many one year and ninety-day men went home. The draw down in man power and influx of new units saw the Iron Brigade re-designated as the First Brigade of the First Division of the First Corps of the Army of the Potomac. They would now be first on paper, as well as first on the field, in the coming campaign.

The men of the Iron Brigade knew nothing of General Lee’s plans, and continued to rotate on and off of picket duty. They’d built up a congenial existence with their counterpart Confederate pickets across the river, often conversing with them, trading Northern coffee for Southern tobacco, and observing a mutual truce to not shoot at each other. As such, the men of the First Corps knew nothing of their army’s thoughts on those General Lee’s plans, and nothing of what they would be expected to do, until one morning in early June the Confederates across the river were simply gone. The Iron Brigade followed on June 12th, stepping off before sunrise and towards the north. Within hours they halted for lunch, and to take care of some unsettling business: the execution by firing squad of one of their own.

Private James Woods of Company F of the 19th Indiana had a habit of disappearing. He’d left the unit around August 20th and returned in early November, missing both Brawner Farm and Antietam. He’d also disappeared for a period that covered the fight at Fredericksburg, been captured, but had convinced a court-martial of his innocence based upon a story of suffering a near miss of an artillery shell and being sent to the rear by an officer. And then the third time came the morning of the fight at Fitzhugh’s Crossing where the unit had taken to boats and carried Rebel positions across the river. Woods dropped his gun and ran, then was later captured dressed in a Confederate Uniform. One has to wonder if he’d just turned himself in if he’d have received a pardon based on the recent policy on desertion. Regardless if it was because it was his third offense, or if it was because he’d been found in enemy clothes, Private Woods’ time was up.

A general court-martial assembled on May 29th to hear Woods case. The private, who up until then had offered any number of excuses for his three absences, everything from being wounded, being ill, and simply getting lost, this time only told the truth. “I can’t fight,” he stated to those assembled. “I cannot stand it to fight.” “I am perfectly willing to work all my lifetime for the United States in any other way but fight,” “I was always willing to try to fight for my country, but I never could.”

Quick deliberation by the court found Woods guilty of desertion; the penalty was “to be shot to death with muskets”. General Hooker approved the sentence and dictated that it be carried out on Friday, June 12th, between noon and 4 p.m., wherever the division may happen to be.

Woods was immediately turned over to the Provost Marshal Clayton Rogers and remained in custody until the 12th. The 7th Wisconsin’s chaplain spent most of June 11th with Woods, and stated that “his firmness, composure and naturalness is astonishing.”

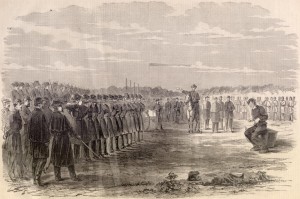

Woods rode in an ambulance that morning as the unit marched north, following Lee into Maryland and into what most now knew was a second invasion of the north. Reports vary if his coffin had already been constructed and was in the ambulance with him, or if it was constructed quickly on the site of his execution. Regardless, once the division had eaten lunch, the entire unit was mustered into ranks in a large U shape, with Woods, sitting on his coffin, at the open end.

The executioners were selected from the five regiments of the brigade. Of the twelve shooters, one would have a musket loaded with only a powder charge and no bullet. None of the shooters thought this would do much good in hiding the facts, as they’d all shot a properly loaded gun, and one with only a blank charge before, and the difference in the kick of the weapon would make it easy to tell the difference.

Woods sat on the edge of the open coffin. Rogers blindfolded the prisoner — even though he requested not to have his eyes covered — pulled open his shirt, stepped aside, and gave the order to fire. The soldiers – some stated they looked worse for the experience than the condemned – fired. Only four of the ten shots hit Woods. Rogers called up one of the reserve shooters. The soldier took careful aim and fired a single shot into Woods twitching body, ending his life.

Woods was put into his coffin, the lid nailed shut, and buried where he fell. At that time in June of 1863 the area was an open field. In recent years I’ve discussed the likely location of Woods with several Iron Brigade and Civil War historians, and while his body has never been officially sought out, the general consensus is that he likely lays forgotten under a parking lot or in a housing development back yard in the suburbs of the Washington D.C. and Alexandria area.

The execution served as a warning to others in the Army of the Potomac against the desire to run from a fight. They’d often said that “No man can fight when surrounded by cowards”, and all knew that the only thing one could depend on in a fight was the man on either side of you. What if that man ran? But the execution of Private Woods put the tangible cost to them all: while it was a bad thing to run in the past and let your friends down, from then on it would be deadly, too.

Once Woods was in the ground, the unit marched once more. They spent the next several days heading north, sometimes so fast and under such harsh conditions that some men would not only fall out due to the heat and dehydration, a few members of the division actually died of heat stroke. Their track kept them close to roads they’d marched before, and with the thought of Second Bull Run – where the armies fought on the same fields twice — the soldiers began to worry that they were simply heading to a reunion with the Confederates on the fields around Antietam. At one point they made camp only two miles from the location of the South Mountain battle the year before. Some of the veterans of that fight visited the rocky mountainside field, looking for the graves of fallen friends. That was all they were willing to do, though, and as they looked over the mountains towards the west where Sharpsburg and Antietam creek lie, many said they’d never fight there again. The horror there was still too fresh, and the shock of seeing Woods shot dead by his own might not have been enough to keep them from simply dropping their guns and going home, rather than fight in the Cornfield again.

But with the next morning the army moved again. Towards the north. Towards Pennsylvania.