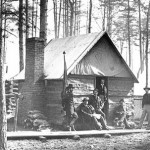

January 1863 saw the 19th Indiana and the Iron Brigade in winter quarters, camped at Bella Plain, VA, on Potomac Creek. Still smarting from the defeat at Fredericksburg, many referred to the winter of 1862-1863 as “the Valley Forge of the Army of the Potomac”. The soldiers built wooden cabins that they fitted with fireplaces and covered with their field tents, then settled in for several months of inaction.

With little to do, talk among the soldiers turned to the recent Emancipation Proclamation. Most were against it, in the respect that they thought it changed the course of the fight. A Captain of the 19th wrote “I dont want to fight to free the Darkeys. If any body else wants to do so, they are welcome to come and do so.”(sic) The near-general consensus throughout the unit and most of the army was that they had signed up to restore and preserve the Union, not free slaves. Obviously little thought was given to the main reason that had caused the war and brought them to that place. Still, others welcomed the proclamation and couldn’t wait to get freedmen in the army, carrying guns and fighting for their own freedom, if only to bolster the dwindling ranks. As with most things political during a time of war, the soldiers soon lost interest even in this topic. Letters home and interviews with correspondence spoke often and heatedly about the Proclamation, either pro or con, for the first few months of 1863, but then as spring came around, it all but disappeared from most records.

Besides discussing the changing political aspects of the war, the men had picket duty around the perimeter of the army. Units spent days at a time on guard, camping in outposts, barns, or out in the open if the weather cooperated. Most considered it a nice change from the camp routine of standing duty, inspections, chopping wood, gathering water, and occasional kitchen duty.

When not on official army business, many spent their idle time drinking and gambling. Stills brewed alcohol from whatever could be found and spared; the German members of the units brought their old-world skills to this with a relish. Concoctions such as “Tangle Foot”, “Splitting Headache”, and “Dead on the Floor” permeated the camps, even though technically illegal. Games also figured largely to fill time: chess, dice, baseball (weather permitting), and cards.

could be found and spared; the German members of the units brought their old-world skills to this with a relish. Concoctions such as “Tangle Foot”, “Splitting Headache”, and “Dead on the Floor” permeated the camps, even though technically illegal. Games also figured largely to fill time: chess, dice, baseball (weather permitting), and cards.

These distractions didn’t ease the major concern of that winter, though: Desertion. As Private John Hawk wrote “the Grand Army of the Republic has one third playing cards, the other doing duty, and the last third deserting as fast as they can”. Even though the 19th Indiana and the Iron Brigade had seen little action at the Battle of Fredericksburg the month prior, they still felt the sting and depression of the crushing loss of that battle. Coupled with the cold and the absence of so many friends around the fireplaces — the unit had lost over 60% of its men to wounds, disease, and death since they’d mustered in less than two years before — the mood took the men to low places in their minds, and many of them simply ran. Rates of desertion varied, some with over two-dozen men missing during the month of January, while the Nineteenth Indiana at one point had nearly fifty men missing. Some had deserted prior to Antietam and were still missing.

Reinforced picket lines made it more difficult for deserters to get out, but some built rafts and rowed across the Rappahannock before changing to civilian clothes to make their way home. For those caught, a trial would be held, with punishment going all the way from extra duty and forfeiture of partial pay, to the extreme cases for repeat offenders (some men had run from more than one battle) of being drummed out of the service, or even execution. One mass drumming-out occurred on February 21st, when seven members of the Iron Brigade were formed up as their comrades stood in formation completely encircling them, and watched as their heads were shaved, the buttons tore from their coats, and were discharged from the service.

As others ran, other soldiers returned to their units. William Ray, of the Seventh Wisconsin, had been wounded at Brawner’s Farm in August of 1862, when a spent-ball struck him in the back of the head and he “spun around on my heels like a boys top and fell with my heels in the air and spun around again for a few seconds”. Ray spent the rest of 1862 in the  hospital recovering from what now would be classified as a concussion. He recovered, and stood guard duty for the brief periods he could stay on his feet, enjoying an actual bed with linens, a bathroom with hot and cold running water, and more than he could eat. On January 6th he volunteered to return to his regiment, instead of waiting for a doctor’s release as most others did, and rejoined the 7th Wisconsin after four days of travel. He found his company that had started the war with 100 members now, “numbered 40 men, which was much larger than I expected to find”. Most of the wounded from Brawner’s, South Mountain and Antietam that would return to their units would do so during the early months of 1863 as the army sprawled in camp along the Virginia countryside.

hospital recovering from what now would be classified as a concussion. He recovered, and stood guard duty for the brief periods he could stay on his feet, enjoying an actual bed with linens, a bathroom with hot and cold running water, and more than he could eat. On January 6th he volunteered to return to his regiment, instead of waiting for a doctor’s release as most others did, and rejoined the 7th Wisconsin after four days of travel. He found his company that had started the war with 100 members now, “numbered 40 men, which was much larger than I expected to find”. Most of the wounded from Brawner’s, South Mountain and Antietam that would return to their units would do so during the early months of 1863 as the army sprawled in camp along the Virginia countryside.

The only real activity of the winter, besides occasional picket duty, was the infamous “Mud March”. General Burnside, looking to redeem himself for the spectacular defeat at Fredericksburg, planned to move the army across the Rappahannock and attack Lee’s unsuspecting forces, also in winter quarters. Mother Nature hadn’t been at the war council, though, and turned loose one of the worst rainstorms in memory shortly after the army moved on January 20th. After three days of men marching in mud up to their waist, puddles of water that swallowed entire wagons, and progress so slow that dogs that served as company mascots had to stop and wait for the men to catch up, Burnside called off the campaign and all returned to camp.

The Mud March proved the end for Burnside. Lincoln replaced him with Fighting Joe Hooker on January 26th. This surely proved a relief to Burnside, seemed a great opportunity to Hooker, and more of the same to the men of the army. Simply another general gone and come. As one soldier wrote, “Well, perhaps it is best to give them all a trial — it only costs fifteen or twenty thousand lives to take each one on trial; so we may as well try them all, while we are about it.”