150 years ago tonight the Union 205 foot long sloop of war USS Housatonic reeled from an explosion and sank off the coast of Charleston, South Carolina. The shallowness of the water, only about 25 feet deep, would save most of Housatonic’s crew. They climbed the masts and into the rigging to await rescue, only 5 out of a crew of 155 lost their lives. As one of the survivors, Robert Flemming, clung to the rigging waiting for rescue, he saw something low on the water: a blue light. He didn’t know it then, but he was witnessing the pre-arranged signal from the Housatonic’s attacker, the submarine CSS Hunley, signaling those on shore that she’d sunk a Union warship. Hunley and her crew were the first in the world to do so, but the celebration would be short-lived. Seamen Flemming saw the signal, several on the shore saw it as well, but no one would see the Hunley or her crew again for 131 years.

150 years ago tonight the Union 205 foot long sloop of war USS Housatonic reeled from an explosion and sank off the coast of Charleston, South Carolina. The shallowness of the water, only about 25 feet deep, would save most of Housatonic’s crew. They climbed the masts and into the rigging to await rescue, only 5 out of a crew of 155 lost their lives. As one of the survivors, Robert Flemming, clung to the rigging waiting for rescue, he saw something low on the water: a blue light. He didn’t know it then, but he was witnessing the pre-arranged signal from the Housatonic’s attacker, the submarine CSS Hunley, signaling those on shore that she’d sunk a Union warship. Hunley and her crew were the first in the world to do so, but the celebration would be short-lived. Seamen Flemming saw the signal, several on the shore saw it as well, but no one would see the Hunley or her crew again for 131 years.

During the following weeks at the Union Navy inquiry into Housatonic’s loss on February 17th, 1863, submarines were not discussed. It would be some time before the submersible CSS Hunley was mentioned and associated with the historic attack, and longer still until all realized that first successful submarine sinking of an enemy vessel in history had been carried out. While many submarines had already operated during the war, for both North and South, they were little known, and then mostly through vague rumors and suspect newspaper articles, and none had ever sunk an enemy vessel.

Like many American Civil War innovations, submarines were not new. Ideas for, and verifiable reports of the craft can be traced back to the 17th century and earlier, with military versions appearing in the American Revolution, War of 1812, and the Crimean War. Even though none of these had sunk an enemy ship, when war broke out in North America in 1861, plans for the “fish boats” came up early. In both North and South, submarines appeared for the reasons that ironclads had come about: the Union’s fear of the ironclad CSS Virginia, and the Confederacy’s need to break the blockade.

The Hunley’s lineage began in late 1861, around the same time that the first Union submarine, the Alligator, took shape at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. In New Orleans, Horace Hunley joined Baxter Watson and James McClintock, two steam gauge manufacturers, then building a submarine ram named Pioneer. The craft’s 30 foot cylindrical hull was pointed at both ends, to ram targets from underneath. An explosive charge was also carried on its back, to be attached to an enemy ship with screws. The crew — one commander and two crew to turn the propeller crank — had no external air source, which limited their time underwater. Tested successfully in the rivers around New Orleans, Pioneer was scuttled in 1862 during the Battle of New Orleans. Recovered and studied by the Federals, she was sold for $48 in scrap in 1868.

After New Orleans’ fall, Hunley and his compatriots moved to Mobile, Alabama. They built another sub, the Pioneer II, and sought to solve the submarine propulsion issue. At that time, men turned a hand crank to power a propeller, which worked well enough, but a larger boat, or need for more speed, required more men, who used up the oxygen faster. Electrical power seemed the solution, yet tests proved the day’s electrical motors unequal to the task. With time an issue, they went back to muscle power, and while tests with the Pioneer II showed promise, she sank in an accident in 1863, forcing the builders to start over once more.

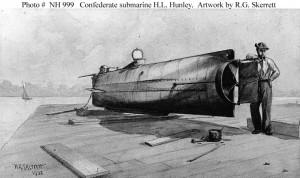

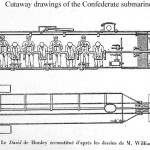

Hunley and team’s third time would be the charm: the Hunley. At nearly forty feet long, she required eight men to turn her propeller. Built in Mobile, she was transported on two modified train cars to Charleston in the summer of 1863. Once there, she immediately proved more dangerous to her crew than the enemy. On August 29th, she sank while tied up to a pier and took 5 men to their deaths. Raised, cleaned, and repaired, she again sank during dive practice on October 15th, this time killing all eight men aboard, including her namesake Horace L. Hunley. Raised once more, a new volunteer crew began training with the submersible.

Hunley and team’s third time would be the charm: the Hunley. At nearly forty feet long, she required eight men to turn her propeller. Built in Mobile, she was transported on two modified train cars to Charleston in the summer of 1863. Once there, she immediately proved more dangerous to her crew than the enemy. On August 29th, she sank while tied up to a pier and took 5 men to their deaths. Raised, cleaned, and repaired, she again sank during dive practice on October 15th, this time killing all eight men aboard, including her namesake Horace L. Hunley. Raised once more, a new volunteer crew began training with the submersible.

Hunley’s methods of attack varied during her testing. Initially she was to dive underneath a target, towing a floating explosive charge on a length of rope that would collide with the ship on the surface. This method had been tested many times successfully, but once Hunley began training in Charleston Harbor, the currents tended to float the explosives into Hunley more than into any intended target. Next they tried a variation on a spar torpedo, which would be rammed into the side of a ship, stuck there by spikes in the explosive’s casing. The Hunley would then back-off from the target, the torpedo connected to a rope on a spool that would pull taught and detonate the charge. For years it was thought that this was the method employed during the attack on Housatonic, but with the recovery of Hunley’s wreck, no trace of the spool was found. Just last year archeologist studying the spar found evidence that she made the February 17th, 1864, attack with a simple spar torpedo: essentially a bomb on a stick.

When that spar torpedo slammed into the side of USS Housatonic off the coast of Charleston, the Union 205 foot long sloop of war sank in less than five minutes, killing five crewmen. The Hunley’s victory was short lived, however, as the sub never returned to base. Even though located and recovered in the year 2000, examination has provided little evidence as to why Hunley sank, taking her third crew to their graves.

After Hunley’s attack, other submarines were built, both North and South, but none ever made another successful attack. Interest in the craft waned as the war did, also, as the North didn’t need experimental craft to continue the fight against an already defeated enemy, and the South didn’t have the resources or organization to make them in any number. The impact of submarines on the war effort was minimal, and while Hunley came out as victor in battle, with her overall record of twenty-one Confederates killed inside her, against five Union dead on the Housatonic, neither side could afford many such “victories”. But 150 years ago tonight, the first successful use of a submarine in combat planted the seeds of what would become one of the most effective weapons of modern warfare.

After Hunley’s attack, other submarines were built, both North and South, but none ever made another successful attack. Interest in the craft waned as the war did, also, as the North didn’t need experimental craft to continue the fight against an already defeated enemy, and the South didn’t have the resources or organization to make them in any number. The impact of submarines on the war effort was minimal, and while Hunley came out as victor in battle, with her overall record of twenty-one Confederates killed inside her, against five Union dead on the Housatonic, neither side could afford many such “victories”. But 150 years ago tonight, the first successful use of a submarine in combat planted the seeds of what would become one of the most effective weapons of modern warfare.